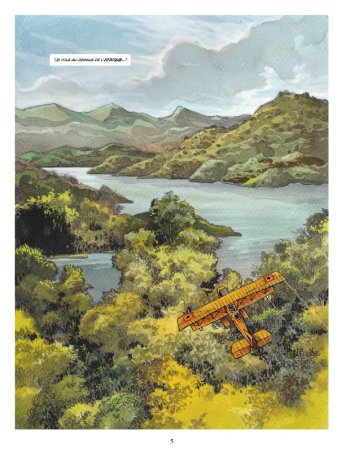

Soaring high over the African landscape in his Short Admiralty 184 seaplane, Gaston Mercier, an officer and a pilot in the Royal Belgian army, marvels at the beautiful flora and fauna below him and the blue African sky above him in the opening pages of Madame Livingstone: Congo, la Grande Guerre. And though he descends and lands on Lake Tanganyika to arrive at Albertsville in the Belgian Congo, this bande dessinée strays far from the trappings of an exoticized, colonialist vision of Africa as the Dark Continent. Rather, it features a story of friendship that sheds light on a forgotten dimension of the Great War (1914-1918).

Soaring high over the African landscape in his Short Admiralty 184 seaplane, Gaston Mercier, an officer and a pilot in the Royal Belgian army, marvels at the beautiful flora and fauna below him and the blue African sky above him in the opening pages of Madame Livingstone: Congo, la Grande Guerre. And though he descends and lands on Lake Tanganyika to arrive at Albertsville in the Belgian Congo, this bande dessinée strays far from the trappings of an exoticized, colonialist vision of Africa as the Dark Continent. Rather, it features a story of friendship that sheds light on a forgotten dimension of the Great War (1914-1918).

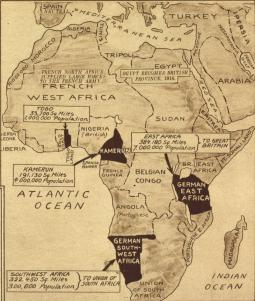

Set in what is now the eastern region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madame Livingstone follows Gaston Mercier who befriends the intelligent and mysterious Madame Livingstone, a kilt-wearing local who claims to be the métis[1] son of famed Scottish explorer David Livingstone, while the two search along the Congo river and Lake Tanganyika for the feared German warship the Graf von Götzen[2] in order to sink it. Through his friendship with Livingstone, Mercier discovers an Africa far removed from the exotic images in circulation in Europe and from the assumptions undergirding the entire Belgian colonial endeavor and social hierarchy. As a result, Mercier—a proxy for readers—begins to question the ethical framework of European colonialism in general and the treatment of the local population by European colonists in particular. Indeed, after working with Madame Livingstone, Mercier voices his concerns and often attests to Livingstone’s intellectual acuity and charisma, much to the disdain of his countrymen from Belgium and his commanding officers.

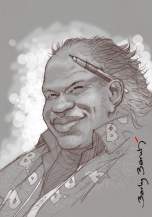

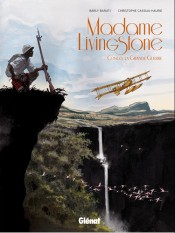

Published earlier last month by Glénat in conjunction with the 100th anniversary[3] of the beginning of World War I, Madame Livingstone—masterfully illustrated by celebrated Congolese artist and musician Barly Baruti and written by Christophe Cassiau-Haurie from a story by Apollo—delights with the beauty of the central African landscape while plunging into the rich sociocultural complexity of colonial life in the Belgian Congo.

Much of the joy of reading Madame Livingstone derives from Barly Baruti’s intuitive use of space on the page and from his deft blending of sumptuous landscapes, subtle facial expressions and body language, and well-researched and well-executed historical accuracy. His combination of a couleur directe aesthetic[4] and a dynamic deployment of varying panel sizes and splash pages adds a dramatic flair to this bande dessinée. From the cover to the bonus section (“Madame Livingstone: études et recherches”), Baruti keeps readers enthralled and entertained while Christophe Cassiau-Haurie’s script engages them in a closer look at the Belgian Congo during this historical moment.

Indeed, Cassiau-Haurie’s humanistic rendering of this century-old epoch serves as the driving force for Baruti’s expressive artwork. Cassiau-Haurie succeeds in generating relatable main characters who are ambitious, intelligent, and independent and who also have their flaws. Put another way, Mercier and Madame Livingstone come across as real, complex individuals rather than categorical stereotypes of colonizer and colonized. Furthermore, through dialogue Cassiau-Haurie reveals the uneasy tension underlying Europeans’ presence and ambitions in central Africa.

In addition to demonstrating interpersonal relationships in the Belgian Congo, Cassiau-Haurie and Baruti also challenge preconceived notions about indigenous populations and, in doing so, offer a vision of central Africa in which the effects of globalization predate the arrival of European colonists. This is most effectively conveyed through the character of Madame Livingstone himself. Visually, he embodies cultural hybridity and a keen sense of capitalistic aptitude; his trademark kilt and traditional Scottish attire he acquired from Scottish soldiers in the British army in exchange for cases of Belgian beers. Similarly, he manifests fluency in many different African and European languages as well as being literate, well-informed, and extremely intelligent. In fact, he is able to see much more clearly than Mercier in both a literal and figurative sense—a fact that Mercier discovers and greatly admires.

Though Madame Livingstone tells the tale of a unique and intense friendship during the Great War, it also speaks to the contemporary moment. In many ways, Mercier and Madame Livingstone stand in for Cassiau-Haurie and Baruti themselves, a correlation corroborated in the bonus section and by the authors themselves on social media. The fictional friendship in Madame Livingstone and the real friendship between the authors points to an intimate relationship between Europe and Africa, one that has a long history, and invites readers to reflect on the nuances and complexity of such a history.

[1] Ethnically-mixed.

[2] This is the very same ship at the heart of C. S. Forester’s 1935 novel The African Queen, which was later adapted in 1951 by director John Hughes into the film classic of the same name famously starring Humphrey Bogart and Katherine Hepburn.

[3] TV5Monde, upon the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the start of WWI, has created an interactive website that explores the Great War through art (1914-1918: La Grande Guerre à travers les arts) with one section, La force noire, dedicated to the contributions of African soldiers in the war.

[4] Couleur directe is a technique in which artists apply color directly to the original drawings, thus transforming each page and each panel into a veritable painting.